Through her Evolutionary Anthropology Classes, Elaine Guevara Invites Students to Take a Side Door to STEM

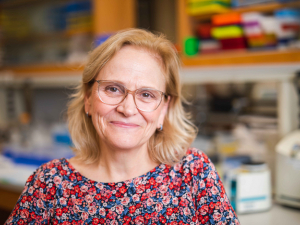

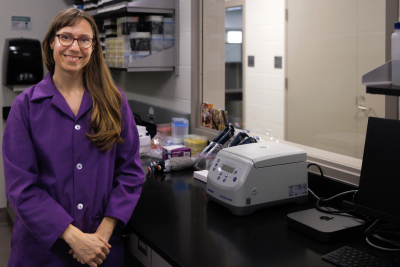

Elaine Guevara doesn’t shy away from difficult conversations. As a lecturer in the Evolutionary Anthropology department, she weaves evolution, genetics and physiology with history and ethics, tackling head-on problematic interpretations and aspects of human evolution research to give students tools to identify and debunk racist scientific ideas.

Guevara first joined Duke in 2019 as an assistant research professor of Evolutionary Anthropology, a position where she combined teaching and research. She started as a lecturer in the Fall 2022.

Guevara has sought to decolonize Evolutionary Anthropology and make the field more welcoming to students of historically excluded backgrounds. Most recently, this includes launching a new summer internship program for students from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Guevara, along with other members of the Evolutionary Anthropology department, including Leslie Digby, associate professor of the practice, Brian Hare, professor and chair, Doug Boyer, associate professor, graduate students Alma Solis and Alisha Anaya and postdoctoral researcher Madelyn Crowell, was recently awarded a Duke Faculty Advancement Grant to support the internship. .

We sat down with Guevara to discuss her transition from research to teaching, as well as the role of Evolutionary Anthropology classrooms in combating racism.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How do you describe your work as an Evolutionary Anthropologist?

Maybe molecular primate evolutionary ecology? I use a lot of molecular methods — DNA and physiological biomarkers — but don’t consider myself a molecular biologist. I’m a primatologist, but I have never studied behavior!

I am interested in sensory and dietary ecology (how different individuals and species taste, smell and see the world, and how that coevolves with their diet) and aging (why do some individuals and species live longer than others? To what degree are patterns of senescence universal?).

This wasn’t your first year at Duke, but it’s your first year as a lecturer. How has to the transition from the lab to the classroom been?

You know, through most of my training, I would have said my dream job would have been pure research. But it turns out that I really love teaching! Humans are social creatures and most of us are really motivated by sharing experiences and ideas, as well as helping and learning from others. It is really cool how much I learn from my students.

I think I liked the idea of research more than I actually enjoyed the day-to-day. After toiling in relative solitude for several years in graduate school and as a postdoc on research that seemingly moves slower than molasses, I realized it was hard to sustain the pep in my step. It is astonishing how good it is to have interpersonal exchanges in my work life again. I so enjoy discussing tough questions about human and primate evolution and health with Duke students.

All that said, I would never trade the years I spent focused on research. I find them fundamental to interpreting the current literature to keep my class accurate and up-to-date and answering students’ questions. And I admit I’m still the person who is excited to get out of bed on Saturday morning to read academic journal articles. I think I also have more good research ideas now because teaching has broadened my thinking and rekindled my creativity.

What courses have you been teaching? And which students would benefit from taking them?

I teach the big introductory course, Introduction to Evolutionary Anthropology. It is exciting to introduce students to a lot of new things — from the fossil record, to how carbon-14 dating works, to why copious sweating is a human superpower, to why most of us adults can’t digest milk. Anyone would benefit from this course! Especially anyone who is STEM-curious but maybe not STEM-confident. Evolutionary Anthropology can be a side door to STEM for students who come into college without a lot of STEM background or even some negative experiences with math and science, unfortunately all too common, but who are curious about the natural world. That was me!

I also teach Human Biological Variation, a seminar that dives deep on evolutionary and physiological variation in our species and gets into timely questions like whether genetics should be considered in assessing medical risks, which human groups have been exploited in — versus primarily benefit from — human biology research and our how social environment influences our health. I would especially recommend it for anyone pre-med.

Finally, Evolutionary Biology of Aging, another seminar, is the first class I actually pitched, so it’s my special pet. Perhaps humdrum sounding on the surface, aging is actually a remarkable, outstanding puzzle in evolutionary biology. In our exploration in this class of why some species live longer than others, we discuss reproductive biology, social behavior, learning and memory, why elephants don’t get cancer and what naked mole rats and trendy skin care products have in common. I would recommend the course for literally anyone because, guess what? We are all aging.

Evolutionary Anthropology has a troublesome and often racist past. You have led or been involved in multiple efforts to address this problematic history and its consequences. Can you tell us more about that?

Society has a racist past and present, and evolutionary anthropology has played a special role in that as the source of scientific authority on human evolution, both for ill and good. Some 19th-century anthropologists like Samuel Morton were concerned with “scientifically proving” the theory of polygenism — the idea that human races have different origins, that was developed to justify the violent displacement of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of people of African ancestry in the Americas. Some 20th-century anthropologists, like W. Montague Cobb, tirelessly combated such biological hypotheses of racial difference. Contemporary evolutionary anthropologists are uniquely well positioned to address and debunk “race science.”

Yet when I first started teaching, I didn’t discuss race much because I considered the case closed: race is a social construct and not a biological reality. However, with the rise of genomics and the use of ancestry in medicine and direct-to-consumer testing, not to mention the increasing mainstreaming of white supremacy, I realized it was not only necessary but urgent to talk about race in any class related to human evolution or biology.

What’s more, I’ve come to view biological race as a “zombie idea” rather than simply an outdated idea. That is, no matter how many times scholars definitively take it out, it won’t stay dead long. It may recede for a decade or so, but will come back in a new form. We can see the Biblical hypothesis of race transform into a phylogenetic hypothesis of race in the wake of Darwin’s influence, which after being demonstrated untenable transformed into a genetic hypothesis of race that was similarly falsified. We are now confronting the genomic ancestry view of race, which holds, incorrectly, that races (reconfigured as continental-level ancestry groups) can be delineated based on variations in allele frequencies at thousands of DNA base pairs across the genome.

Crucially, the inevitable resurrection of biological race is an intentional project, led by people that I call race realists. As race science gets more sophisticated with increasingly large genomic datasets and sensitive analytical methods, our teaching about race needs to get more sophisticated. I have to get into the weeds about how ancestry assignment works and how it (does not) relate to race or even the level of deep ancestry that most people assume. Thus, a lot of my efforts have been around how to best teach this stuff and how to further its reach.